The temple dancers of Greece wave graceful arms as they step lightly round the altar. In Scandinavia warriors dance together, working themselves into a frenzy, to become unstoppable in battle. In large parts of Europe, spring is met with a maypole. People bedecked in greenery dance around it to welcome spring and new life.

Two thousand years ago dance was a part of life in Europe, particularly in the pagan religions, where dance accompanied religious ceremony, fertility rites, battle preparations and more. Dance was less central to the Romans, but they nonetheless danced in procession at agricultural festivals, performed weapon dances for the god Mars, and danced with abandon at big festivals like Saturnalia. Pantomime performances of stories were also a popular pastime for Romans.

Judaism valued dance, but according to strict rules. Dancing was a requirement at weddings, for example, but men and women were separated to discourage lustful thoughts. There were dances for festivals and for harvest, among others. These were to be observed as part of the Covenant with God and those who did not dance would be breaking the Covenant.

Christianity was something new. It would have to find its own rules for dancing.

Early Christians believed the second coming of Christ would be soon. Their main concern was to live a pure life, to make themselves worthy of God. As such there was a lot of debate on what behaviours were appropriate for Christians. Debates which have reverberated throughout the centuries. They denied themselves bodily pleasures. The moral deprivations they saw in Roman society would soon be cleansed by God.

Jesus’ opinion of dance is not recorded so church leaders were left to decide what was and was not appropriate. Early Christians found it hard to accommodate dance in their worship as it seemed at odds with the message of cleansing and purity. In dance the human body jumps, moves, and writhes. They felt the body was not to be glorified in itself; rather, it was a vessel for the soul and should therefore be kept pure. A corrupted body taints the soul and leaves it undeserving of God. Dance was one such way the soul could be tainted.

Whatever early Christian leaders may have wished, converts often came from pagan religions where dance was central to worship. In other ways pagan converts were accommodated, such as rebranding festivals as Christian ones. And in dance too they had to be accommodated. So slow processional dances, often in circles, appropriate for the ‘pure’ Christians, developed. For example, bishop Basileos the Great (344-407) referred to a circle dance when he wrote “Could there be anything more blessed than to imitate on earth the ring dance of the angels?”. Labyrinth patterns were laid out on many church floors, on which the processional dances were performed. Women dancing, however, were seen to pose a temptation to men, and were encouraged not to dance. The same bishop told women “you should more properly bend the knees in prayer.”

Solemn in intent these dances may have been, they had a tendency of getting out of control. St Augustine disapproved of dance for this reason, seeing dancers forget they were on consecrated ground, and dance inappropriately. Leaders could control what art and music were allowed into the church, but the dancing body was unpredictable. The church councils wanted to ensure that nothing could distract the congregation from worship. Wild dancing, they considered, could tempt and corrupt others, and soon dancing became associated with the devil instead of the aforementioned angels. Bans on dancing were issued again and again over the centuries, and again and again, were ignored.

Charlemagne, Holy Roman Emperor in the early 9th Century, banned all forms of dance. But his people were too used to dancing. Their use of dance in religious rites on feast days were versions of the former pagan rites. The dancing continued but it became less and less associated with religious purposes. So dance became secularised.

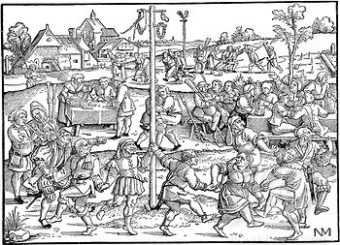

All Hallows Eve is famously a pagan festival appropriated by Christianity. The dressing up and partying with abandon involved continues to this day. Carnival is one festival largely forgotten now, that was huge in the Middle Ages. A great many carnival street events still exist in Europe, mostly in Catholic areas, but the religious connection and wild abandon involved have been largely lost. Carnival was a last chance to eat and drink what you liked, party and make merry before the long austere period of Lent. There were many regional variations, as pre-existing folk and pagan festivals were assimilated, but most generally involved a parade, street party, masquerade and street events such as throwing oranges (Irea, Italy) or horse racing (Rome, Italy). Carnival was banned repeatedly over the years, but to no avail.

Ecstatic mass dances called danse macabre (dance of death) and St Vitus’ Dance emerged in the 11th century and spread throughout Europe. People danced together in churchyards, despite the practice being forbidden. People danced wildly with frantic, jerky movements, foamed at the mouth and appeared to be possessed. It is thought these days that the dances developed to express the epileptic-like seizures of the Black Death and to “sweat out” the infection of of spider-borne tarantism. The Black Death ravaged Europe, killing millions of people. Groups of flagellants appeared, men and women who whipped themselves while walking in processions and circle dances. They did this as an appeal to God to end the plague.

Christianity developed so that one only worshiped in a church and only directed by a priest. This led the way to the separation of the secular and the spiritual, which meant that what was forbidden in church was not necessarily forbidden in daily life. People danced at gatherings and festivals, even if the church councils would rather they didn’t. Over the centuries the separation of secular and spiritual led to the development of secular dance tradition in Europe such as performance dance, folk and social dancing, which would itself lead to the development of ballroom dance. Dancing nevertheless went on in church, despite the many and repeated bans, up until the Reformation.